The Best Evidence for Antidepressants Has Never Been Published...and Never Will Be

For practicing clinicians, the jury on antidepressants came in a long time ago.

Public discourse questioning the effectiveness of antidepressant medications is rising again, and skeptics now have an unexpected ally in the US government as RFK Jr. takes the reins as Secretary at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This will likely serve as additional fuel for an already misguided cause. Antidepressants are on trial again.

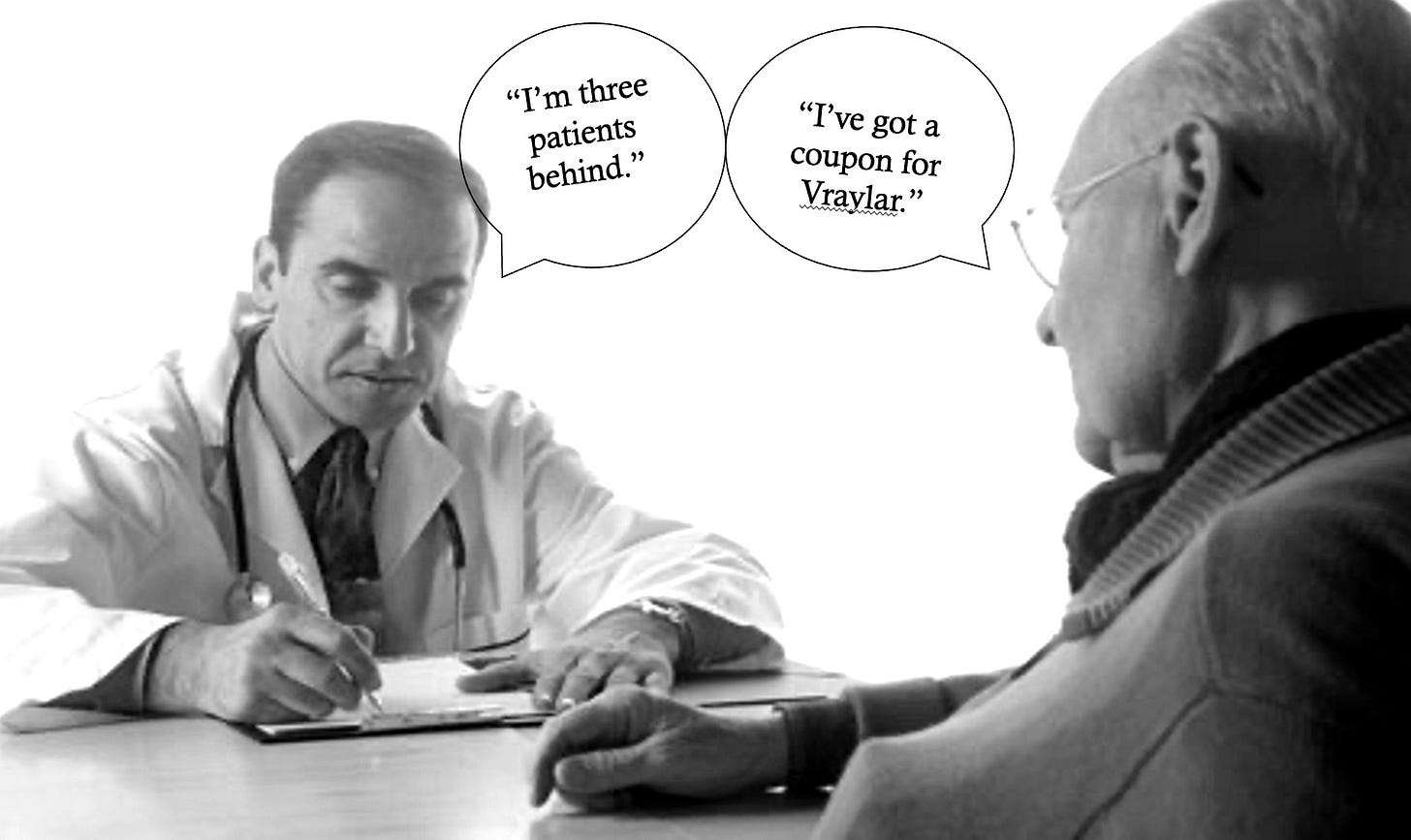

Debates about antidepressant efficacy are not new, but they’re almost always focused on the published research. This is understandable, because that is the information available for scrutiny, specifically by those who don’t have direct experience prescribing or taking the medicines. Most of the published clinical trials studies show only marginal benefits of the medicines. This research, however, plays a minimal role in the day-to-day decisions of clinicians.

Physicians and nurse practitioners who prescribe antidepressants (around 85-90% of whom work in primary care) do not doubt the effectiveness of the drugs at all. Neither do most of the approximately 40 million adults in the US and 9 million in the UK who take the medicines every day. Providers don’t ignore the research, but the published outcomes data means little compared to the actual results they see in the individual patients they know and treat. Results seen in a doctor’s office eclipse the outcomes data in any study, no matter how well-designed or extensive it is.

BY THE NUMBERS: THE ACTUAL EVIDENCE

A full-time primary care clinician working in an outpatient practice sees an average of between 20-30 patients per day. That’s over 100 patient visits per week, about 5000 in a year. For around 10 percent of these visits, a mental health issue will be the primary reason, and a substantial portion of other visits (for other reasons) will include an antidepressant medication initiation or adjustment. This totals 4000-5000 patient visits in a year, and at least hundreds of these will involve seeing a patient who takes an antidepressant.

Outpatient psychiatry practices vary greatly by setting and patient population. Even the shrinking portion of psychiatrists who identify primarily as psychotherapists still prescribe medication to most of their patients. A majority of psychiatrists (and almost all psychiatric NP’s) specialize in providing pharmacologic management. Depending on the setting, a psychiatric practitioner may see as few as 10 and as many as 20-25 patients in a single day, and at least half of those patients will be on antidepressants. In one year these psych providers will participate in at least a thousand meetings with patients taking an antidepressant medication. Even though I identify primarily as a psychotherapy psychiatrist, a spot check of my January 2025 calendar as I write shows I participated in 68 interactions with patients on antidepressants.

Combining these two areas of medicine, primary care and psychiatric providers will have had thousands of encounters with patients on antidepressants in just their first couple of years in practice. They will see full and partial remissions, non-responders, side effects, and negative reactions. In the life of a practicing clinician, who has to assess a condition and launch a treatment plan, these interactions with patients are the main source of input to that process. Astute clinicians stay up to date with the medical literature and are aware of published study outcomes. By necessity though, they’re also doing “their own research.”

How can doctors be so confident the medications work? This may sound too simple to be helpful, but it’s because our patients tell us.

How can doctors be so confident the medications work? This may sound too simple to be helpful, but it’s because our patients tell us. It isn’t much different than when a patient reports that their hip pain is a lot better since physical therapy, or their reflux is better since cutting back on coffee. Doctors listen to their patients. Patients know how they’ve been feeling and thinking. We also observe our patients. We watch severe anxiety morph gradually into calm. We see a face full of anguish and pain turn into relief, or even a smile. We see someone who just a few weeks ago could barely move from the chair, spring right up to greet us in the waiting room. We see and hear the relief in their spouse, parent, or friend. Dozens, hundreds, thousands of times.

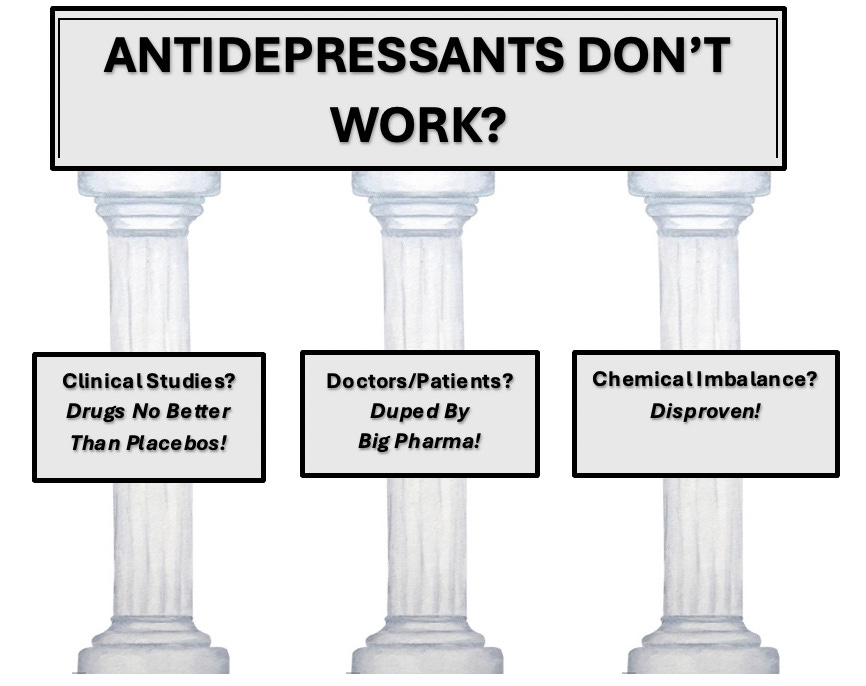

THE THREE PILLARS OF STRAW

Skeptics of antidepressant efficacy begin with the charge that the medicines are overprescribed, dispensed to too many people who don’t need them and who would do better with watchful waiting or some other treatment. These statements all more or less true, but tell us nothing about efficacy for those who do need and benefit from antidepressants.

Among the most common arguments lodged by critics are:

the medicines do only marginally better than placebos in published studies

prescribing practices are unduly influenced by the financial interests of pharmaceutical companies

prescribing is based on a serotonin deficiency or ‘chemical imbalance’ theory, which no longer makes sense since ‘the theory’ has now been disproven

Of course some people take the medicine and will seem better, and it will have nothing to do with the medicine. But this prospect is built into the equation from the beginning. Many patients will return feeling no better, and some come back feeling worse. Some will then seem to get better with the second or third medicine they try, or on no medicine at all.

Antidepressants do appear barely more effective than placebos (or ‘sugar pills’) in published studies. But the results of these clinical studies are NOT the chief source of evidence clinicians use in making prescribing decisions. However, these research results ARE the main source of evidence used to critique claims of efficacy for the drugs.

There is a surprising finding in this research central to this debate.

(For the deeper dive, I highly recommend Ordinarily Well: The Case for Antidepressants by Listening to Prozac author Peter Kramer, MD. We are all indebted to Dr. Kramer for researching and writing this comprehensive book, THE definitive volume on this topic.)

At least two successful studies are required by the FDA for drug approval. These studies are very expensive in time, money and effort to be shepherded through to a conclusion. Critics fairly assume the studies may be slanted in ways to maximize the chances for FDA approval. A 2008 New England Journal of Medicine investigation revealed that many unfavorable studies had been withheld from publication. Of 74 antidepressant studies registered with the FDA in the 1980’s and 1990’s, 31% had not been published.

Not surprisingly, the unpublished studies were mostly unfavorable for the drugs tested. This investigation was widely reported in the news, amplified by public discourse by former NEJM editor Marcia Angell MD, a reputable and outspoken advocate for evidence-based medicine. This ‘file drawer effect’ (when a researcher files away results not supporting a hypothesis or theory) provided additional support for the skeptics. Dr. Angell is right to advise caution in interpreting anecdotal evidence or let it guide decisions. But a doctor’s practice is filled with anecdote every day. “My bowels are more regular”, “my sleep is interrupted”, “the left side of my head really hurts”, etc. are all anecdotes. Once a tall stack starts accumulating in the corner, however, anecdotes turn into actionable evidence.

THE PLACEBOS LOOK GOOD (BY COMPARISON). BUT WHY?

Designed to get approval for the drug, these studies paradoxically end up making the placebo look relatively good, so the active drug looks weak by comparison. Upwards of thirty to forty percent of patients taking placebo “get better” in many of these trials. Outcomes data (the average rating scale score improvement) published are averages, the average including both robust responders plus marginal and non-responders. This is one reason the active drug looks less impressive.

Applying a rating scale scoring as a supposedly objective ‘measure’ of depression is loaded with obvious and serious flaws. Looking just a little closer though we see other reasons the placebo fares okay, in comparison to the active drug.

The most severely depressed individuals are the most likely to respond to medication…but these folks are usually excluded from clinical trials, as are those with complicating other conditions both medical and psychiatric. People who have not responded well to previous medications are often more interested in trying the latest one (and apply to be in a new drug study). The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17 (the most commonly used measure in antidepressant trials) has a total of 17 items in it…but four of these are specifically “somatic” or physical items. Patients taking the active drug in the study are more likely to manifest physical side effects, which will be registered as points on the depression scale.

The manufacturer is seeking FDA confirmation of efficacy…and to pass a safety and tolerability threshold. Medication dosing guidelines in the studies try to thread a needle between efficacy and tolerability, leading sometimes to a tendency to dose more conservatively, and thus subtract from effectiveness.

The active drug is thus handicapped in multiple ways, helping the placebo group look better. Other features of these studies boost the apparent placebo response. Many study subjects have an ulterior interest in qualifying to be included, and most are compensated financially. So there is a tendency to inflate the severity of symptoms on rating scales at the beginning (in order to qualify for the study). Subjects like these (who are not actually ill) receiving placebo will then show improvements on their ratings over time as they feel freer to be more straightforward in their reporting.

The less severely depressed (and the chronically intermittently depressed, dysthymic) may enroll when in a depressive phase, then as a matter of natural mood fluctuation, look better with time (even on placebo). One more vote for placebo is the naturally therapeutic effects of being in the study at all. It’s a bit like being in psychotherapy. Subjects meet regularly with a professional evaluator, who interviews them and asks them questions about their life. They are repeatedly attended to, by an interested other. This is likely to feel supportive and affirming to most participants and show an improved condition by the end.

‘BIG PHARMA’ INFLUENCE MAY NOT BE SO BIG

Another pillar of the argument against antidepressants and an accusation leveled at doctors is that we are beholden to or under the spell of pharmaceutical companies. ‘Big Pharma’ invests billions of dollars marketing to consumers and physicians. This undoubtedly influences both physician behavior and patient expectations.

In a profession with already shaky public credibility, revelations from a 2008 congressional inquiry that several prominent academic psychiatrists had been paid large sums by pharmaceutical company payrolls left a well-deserved stain on the profession. Another study revealed that 60% of DSM-5-TR task force and panel members received financial compensation from pharmaceutical companies, and that these payments were undisclosed. All of this reinforced a public perception that the ever-expanding diagnostic manual was written in effect to promote over-diagnosis and, in lock step, over-prescription. This is a valid criticism and cause for wariness whenever the latest wonder drug arrives on the scene.

These investigations led to a few enhanced ethical guardrails, mostly in the form of financial disclosures required both of speakers and the companies. Layers of influence by those at the top do trickle down to the work-a-day providers in their offices with their patients. Continuing education conferences and practice guidelines have the winds of massive pharmaceutical lobby influence at their backs. But practicing clinicians are just that: practical. We like to make our own decisions and question authority handed down from on high. We too are suspicious of a hotshot department chair from the ivory tower dictating to us. We won’t prescribe a medicine if we don’t see it work.

Flashy ads displaying happy satisfied consumers seek to create for the medication a kind of ‘preemptive reputation’. This dynamic reminds me of comedian Jerry Seinfeld explaining on Fresh Air why, with all his success, he still enjoyed the challenge of doing live stand-up. Because he couldn’t “cheat” or “skate” on his reputation.

Host: “You can’t skate on a reputation in a live club. Even if you’re Jerry Seinfeld.” Jerry:“They may give you 3 or 4 minutes at the top; but after a while, no one laughs at a reputation.”

Pharmaceutical company influence isn’t new…it’s been baked in from the very beginning. Along with antipsychotics, antidepressant medications had the fingerprints of pharmaceutical profiteering starting in Europe in the 1950’s. Supplied by Swiss pharmaceutical company Geigy, compound G22355 (later named imipramine) was at first just another in a series of medications that psychiatrist Roland Kuhn administered to patients on his inpatient ward. Geigy worked with Kuhn to test a series of drugs to compete with the highly successful antipsychotic medicine chlorpromazine (Largactil in Europe, Thorazine in the US). Results were generally disappointing, as G22355 had little to no effect on psychosis when given to patients with schizophrenia.

Some of the patients who took it, however, showed clear improvements in mood and energy. In January 1956 Kuhn decided to test the drug on a severely depressed patient, one he knew well and visited multiple times daily. The response was so dramatic in the one patient that with Geigy’s go-ahead he began to treat a group of forty inpatients and clinic patients with melancholia with the new drug. He observed the effects closely for the next year and a half and presented his findings to a group of colleagues in August 1957. Kuhn's brief 1957 paper contains fascinating lessons still applicable to thoughtful diagnostic and pharmacologic practice. An influential Geigy shareholder’s support of the company’s decision to proceed with imipramine was based in part on how well his wife did taking the drug. Drug manufacturers have a vested financial interest in how doctors practice. It is prudent for physicians and patients alike to remain wary about industry motives and claims.

‘CHEMICAL IMBALANCE’ REDUX

Imagine that a fire alarm you’ve never heard before started loudly blaring right now, wherever you are. There would be a dramatic change in your feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. You would likely find a way out of where you are, to assess the threat and get yourself and others to safety. Now imagine that 24 hours later, a friend asks you “What happened at this time yesterday?”. You could say "I had a chemical imbalance." There would be some truth in this answer. When the alarm sounded there would be a dramatic influx of adrenaline and cortisol (=chemicals) into the bloodstream, shifts in blood pressure, vision, and muscular tone all exquisitely orchestrated by neurotransmitters (=chemicals), a set of physiologic and neurologic processes too numerous to count.

But if that was all you said…if there is no mention the fire alarm, the most influential event would be missing. This is the main problem with the ‘chemical imbalance’ meme. It’s based in a root of truth, but has hardly any usefulness.

Let’s stipulate the obvious. The ‘chemical imbalance’ meme is exploited by pharmaceutical companies as a suitable rationale to take medications. Many clinicians and some health organizations also utilize this meme as a lazy abbreviated shorthand to reassure patients, avoid the responsibility of a more complete explanation and discussion of the complexities of one’s difficulties.

Claiming that depression is caused by a known physiologic disturbance in brain chemistry is indeed a gross oversimplification of a complex set of processes. I encourage clinicians and patients to see their difficulties within a wider bio-psychosocial framework. But it is also unrealistic to claim that depression has nothing to do with fluctuations in neuro-chemical transmission. The evidence for the role of synaptic transmission of neurotransmitters (including serotonin) in mood states is abundant…but it cannot be quantified or comparatively measured by any currently available technology.

A narrative was launched by a review article in Nature (July 2022) by British psychiatrist Joanna Moncrief and colleagues. They summarized a selected review of research on serotonin’s role in depression, received international attention and was well-publicized in mainstream media. From network morning television to local public radio call-in shows, it was news. The 40+ million people in the US and nine million in the UK taking antidepressants were understandably interested. The public’s verdict? There is no serotonin deficiency implicated in depression. Case closed.

For anti-psychiatry activists and select patient advocates, the Moncrief paper has become gospel. To many people it represents settled science. The findings in the paper (a review of selected research already done) are seen as proof that the ‘chemical imbalance’ theory (or ‘low serotonin hypothesis’) was unfounded and untrue. But that isn’t what they said.

Assuming positive intent by Moncrief and colleagues, they went looking for something that hasn’t (yet) been found. They sought evidence for one small piece of a conceptual hypothesis. Having come up empty, they used this “lack of evidence” to knock down a society’s simplified meme about depression. The holes in logic proffered by Dr. Moncrief were systematically dissected and described in this in-depth article by psychiatrist and philosopher Awais Aftab MD.

“NOT TO MY KNOWLEDGE”

When I was a kid, before answering machines or voicemail, we relied on whoever was home at the time to relay messages to us… to either write them down, or just remember. I recall my sister returning to the house, asking “Did Melody (her friend) call?” My dad answered “Not to my knowledge.” In this, his standard response, was a recognition that there was a limit to what he knew. Had he responded “No”, he would be making a claim outside his scope of his known truth. I like saying “not to my knowledge.” It is so widely applicable in life.

Eager interpreters of the Moncrief paper have made claims beyond the scope of their knowledge, beyond the conclusions the authors wrote. The verbiage in the paper confirms this. They “found no evidence” and stated “there is no convincing evidence.” But what the public heard, and the critics have loudly echoed, is “There is no evidence.” In the general public, this may pass as a subtle semantic distinction without a difference. But hearing we “found no evidence” and then concluding “there is no evidence” is a profound difference in the world of supposedly scientific claims, rendering it incorrect on face.

Most important for this discussion is that the underlying premise, that clinicians prescribe antidepressants because of an overly simplistic or erroneous belief about depression in the general public, is false. This belief “provides an important justification for the use of antidepressants.” It is not the reason the medicine is prescribed.

WRAPPING UP

The histories of medicine in general and psychiatry in particular are checkered with a list of some regrettable practices for which a satisfactory atonement is overdue. But the widespread provision of antidepressants to those who need them and benefit greatly from them isn’t on that list.

We can expect the hot potato that is antidepressant efficacy will get tossed around more and more in the coming months. The new HHS default claim is about wanting to see ‘the science’. The scientific evidence regarding antidepressant efficacy is not in the published clinical trials. The best evidence for antidepressants will barely even be documented…and will never be published.

Until next time, thank you for reading.

EPILOGUE: FOR FUTURE POSTS

*Antidepressants are not a panacea… practicing clinicians are well aware of this. A subset of people with depression and anxiety derive no clear benefit from the medicines and will do better with other approaches or watchful waiting. Many people will improve on their own, with no intervention. Many treatment settings do not provide thorough assessment or proper follow up. Though not common, these medicines can have severe side effects and problematic withdrawal effects. Far too few patients receive proper information and guidance for when this occurs. Even though it is a small percentage, with tens of millions of people taking the medicines every day means tens of thousands of people end up in that situation. I will address these specific concerns in future posts.

Lord, it's like reading a hysterically passionate defense of antacids.

I'm a peer worker, and I’m supposed to believe people’s lived experiences, but even I find this stretches belief beyond all credulity. You're talking about the weakest class of psychiatric medication, and your argument rests on reports from the masses of people who crowd doctors offices with common complaints.

Since your entire argument rests on elevating personal anecdotes to the level of detailed case histories, I’ll meet you on the same level:

I don’t know any doctors I respect who believe SSRIs are effective for serious depression. (Sorry Roland)

I don’t know anyone with a clear-cut depressive illness with vegetative features who has benefited from an SSRI.

If we look at the history of primary care, it’s not the birthplace of great ideas. Freud practiced his theories on the wealthy unwell, and family clinicians for centuries swore by bloodletting and purging. We know ECT works because people with melancholia rise like Lazarus. Your demoralized patient sitting a little nervously in the waiting room chair isn’t a proper equivalent to a catatonic person waking up in front of you after lorazepam.

And why, of all drugs, do people rush to defend SSRIs so passionately? (I assume we're not passionately defending imipramine, that would just be too much to ask) Where were all the voices when Moncrieff attacked lithium? Why does Prozac get these long-winded polemics when treatments like lithium, ECT, and benzodiazepines are left to rot? Yes, let’s focus on Prozac when less than half of people with bipolar are even trialed on lithium. I don’t think I go a week without hearing about Lazarus-like recoveries from one of those three treatments. ECT? Sure, heard it many times, another one just last week. Benzos? Absolutely, just don't go bananas. Lithium? People take too much when depressed, but I don’t hear horror stories and I see people get well and stay well. SSRIs? Sure, half of everyone I know takes them, from friends who are totally well to friends who are neurotic. The neurotics swear they work, but they swear everything works, and they swear they have every illness, so it’s impossible to keep up.

Who are these melancholics you’re rescuing with Prozac? Where are they? Name one expert on melancholia who praises SSRIs. I’ve never heard of a serious doctor in acute care using SSRIs for melancholia (except Roland apparently). No academic psychiatrist praises their use. Name one. I’d love to speak to them. I get your argument: they're in an ivory tower, unable to see the work-a-day doctors treating all these gravely ill people with Prozac. Those same work-a-day doctors who can't even tell in their five-minute appointments when Prozac is making a patient agitated, irritable, or impotent. Yes, those doctors primary care doctors, who spend hours taking detailed notes from patients, interviewing family members, and filling volumes of case histories that clearly show the dramatic efficacy of Prozac. Oh, please. You know, many years ago when I was a wee young lad I had a doctors appointment that lasted an entire quarter of an hour. The things he must have learnt in such a time as that, an entire fifteen minutes, well I'm sure they would fill all the medical textbooks of the world.

The reality is: you see the doctor for five minutes, say “I’ve been feeling anxious and depressed,” they give you Zoloft, you take it for two months, it makes it so your dick doesn’t move, you stop taking it, and your doctor has no idea. But they go on thinking they’re doing a wonderful job. Maybe it’s you who needs to come down from the ivory tower. It’s as absurd as not understanding the effects of alcohol. Take one, just take one, and tell me that’s not more or less the experience. I don’t buy the "your mileage may vary" stuff. I'm like you, I accept the reasonable evidence of peoples eyes. Some people are happy drunks, some people are sad drunks, but how much does the mileage really vary? Heroin users give pretty accurate accounts, and yet Prozac’s effects are a mystery? Here's what I think, most people take it, and it does pretty much what I just said, but they never bother telling their doctor. A fairly large number of nervous people take it and swear they feel better—same people who last week told me they have ADHD and Adderall makes them feel better, the same people who tell me about their joint pain, upset stomachs, and how they’re neurodivergent and no one believes them about their back pain. I’m not meant to be saying this, but I just don’t care anymore. I know too many people like this and they are so unhealthy from the medical system. It’s not an uncommon personality type. We all know people like this, and most of them are on some pill or another. Frankly, they’d probably feel better on anything. Multiply that out, and you get a pretty good theory about why these drugs have caught on.

I would suggest the reason SSRIs are so popular is because they don’t do a whole lot, which is absolutely perfect for people who don’t have much wrong to begin with.

The only reason you can give is that millions swear by them. Suddenly there are all these melancholics at death’s door, and Prozac 100% did the trick did it? And everyone was too stupid to notice all these gravely ill people for centuries? We only started noticing once we started giving Prozac to people? Jeez, how about that?

Here is my challenge: I don’t want to see any more RCTs. Just give me a case series—three or four full case histories. I want to see a detailed history of the course of illness, detailed psychopathology demonstrating the existence of a serious form of depression, regular detailed follow-ups, and extensive interviews with close family members, friends, and work colleagues. I want to see the long-term outcome. I want you to buy a cot and sleep in the corridor outside the patients’ bedrooms for, say, a month each. Maybe try having sex with them. If you can show me those things, I’ll relent—no RCTs required. I’m perfectly happy to accept careful, detailed empirical observations. I’m pretty sure the lions share of the observations you’re talking about are careless five-minute med checks.

Those are my anecdotal thoughts. Now, should we have antidepressants? Yeah, doctors need options. I don't know, some people have this kind of rumination thing that, they take an SSRI and they don't have as many thoughts, that's my anecdote. Useful. Sure. Sorry to be an arsehole about it, I just can't understand how recreational drug users can describe drug effect in the most vivid detail and psychiatrists can't even describe the most simple effects. I don't like Moncrieff much but when she describes the effects of SSRIs, it just jibes with reality and the straight forward descriptions I hear most people give. My only critique is that she conveniently forgets a whole bunch of other effects. Including some, which may be of some benefit.

Anyway, it's fun speculating and living in an evidentiary vacuum, we can all come up with the wildest opinions.

Hi, Dr. Beech,

We have not met, but my friend and colleague, Dr. Mark Ruffalo, sent me the link to your posting. There is far too much to say on this topic for a brief space like this, but I did want to commend you for so many of the points you make. Most are very closely aligned with what I have been banging on about for nearly 40 years!

I particularly agree with your valuation and affirmation of the clinician's and the patient's felt experience with antidepressant medication. Thousands of us who have had the privilege of working with desperately ill and suffering depressed patients have seen, over many years, the benefits of these medications. (And yes--we are well aware of the important downsides, risks and potential side effects--nearly all of which can be mitigated and managed with expert care). Furthermore, in my view, there has been far too little emphasis on "quality of life" and too much focus on the Hamilton Depression Scale, in assessing the benefits of antidepressants. [1]

Much more could be said, but I simply wanted to register my agreement with the essence of your article. My own views are well-registered on the Psychiatric Times website, including my most recent posting, much of which resonates with yours.

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/the-ongoing-movement-against-psychiatric-medications

Best regards,

Ron

Ronald W. Pies, MD

Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry

SUNY Upstate Medical University

1. Pies RW. Antidepressants, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Conundrum, and Quality of Life. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020 Jul/Aug;40(4):339-341. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001221. PMID: 32644322.